A foreign policy that puts America’s just interests first did not originate with Donald Trump.

During a summer in which Israel, Iran, Ukraine and Russia dominated the news cycle, this seems easy to forget, although it is important to remember.

“The foreign policy of the United States should, within broad moral limits, be motivated and concerned with our national interest,” Frank Meyer told Henry Kissinger in December 1968.

The letter, one of tens of thousands of missing documents found in a warehouse as part of the investigation for The Man Who Invented Conservatism: The Improbable Life of Frank S. Meyerillustrates that even during the Cold War, rightists understood that the Soviet Union only temporarily reoriented the United States’ role in the world. When it ended, so would America’s active involvement in countries most Americans had never heard of (at least that was the idea).

Kissinger, nominated by President-elect Richard Nixon to serve as his national security adviser shortly before Meyer sent his letter, sought advice from Meyer on what ideas should animate the United States’ dealings with other nations. A few years earlier, he had hosted Meyer as a guest lecturer in his Harvard class and arranged a meeting between New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller and Meyer, his constituent most fiercely critical of him. Kissinger and Meyer occasionally called and corresponded.

But neither had really been a Nixon man. That year, the German Jewish émigré advised Rockefeller, and his old German Jewish friend acted as the most conspicuous supporter among intellectuals of Ronald Reagan’s presidential candidacy. They saw the world differently even if they traced their ancestry to the same basic place.

He National Review The editor wrote to Kissinger:

The social systems of other nations are no concern of our politics except to the extent that they represent an armed power ideologically directed toward our destruction. Active benevolence, charity, also cannot be a goal of foreign policy, since charity is the privilege and responsibility of individual people, not the custodians of money taken from people through taxes; and, in the specific case relevant today – the backward nations – the only serious way to advance their economies, in any case, is through investments under the controls of the market system. Certainly, one cannot distort our politics by taking seriously many unrealistic utopian concepts such as world government.

Donald Trump’s foreign policy represents not so much a departure from the interventionist orientation of George W. Bush, John McCain and Mitt Romney as a return to what, even during the Cold War, amounted to the admittedly temporary position of American conservatives.

The American right wants limited government. Skeptics about the government’s ability to deliver a charter generally do not rationally trust it to remake the Third World in America’s image.

Meyer, a member of the board of directors of the Communist Party of Great Britain in his mid-twenties during the 1930s and later an ally of party chief Earl Browder in the United States, understood the threat the ideology posed to the United States. His “messianic” nature, which aimed at “world supremacy,” he told Kissinger, caused the United States to become involved in the affairs of foreign countries, including Vietnam.

Frank Meyer, above right, at a peace protest around 1934, when he was a member of the Communist Party and working under Walter Ulbricht, who later erected the Berlin Wall as East German dictator. In 1962, conservative Frank Meyer implored Nikita Khrushchev to “tear down the Berlin Wall.” (Photo courtesy of Daniel J. Flynn)

As Meyer explained to a Yale audience during a debate with former Congressman Allard Lowenstein in 1971: “I would oppose the Vietnam War, I would oppose all alliances, any kind of foreign aid, and participation in the United Nations… if it were not for the threat of communism.” He described the Vietnam War as a battle within a much larger conflict and said that “if this were not true, it would all be a farce.”

Later that year, cancer-stricken Frank Meyer wrote his final column “Principles and Heresies” for National Review. There, he imagined a world without the Soviet Union that he had served so zealously for 14 years and then penitentially fought for from the courts, magazine pages, lecterns, and protest lines for the last quarter century of his life.

He noted that “elites who have encountered the obstacle of “a prevailing American desire, dating back to Washington’s farewell address, to stay out of the world’s power struggles, have placed great emphasis on one-world utopianism, on the export of democracy, and generally on acting as social workers for the entire world.”

Meyer considered his approach to foreign policy not novel but inherited. From Washington’s farewell address throughout the new republic’s first century, “restricted” accurately described America’s interactions with the world. He envisioned a day without the disorienting force of the Soviet Union, when the United States could go back to minding its own business without worrying about another nation minding its own business. So the conservative call for limited government could extend beyond domestic spending to foreign policy.

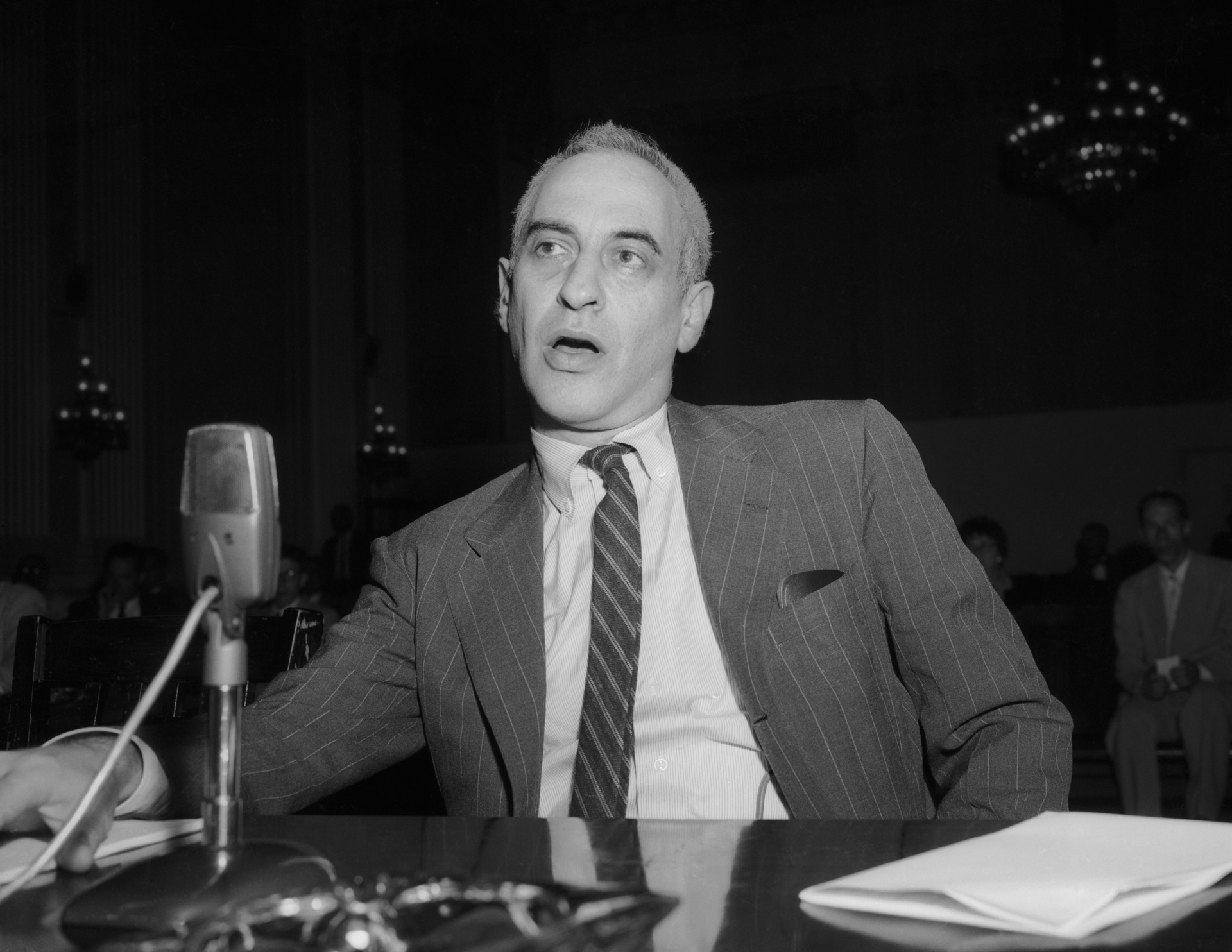

Frank S. Meyer of Woodstock, New York, former Communist Party professor, named before the House Un-American Activities Committee in July 1959 over communists working in education. Meyer said he was a communist from 1931 until he broke with the party in 1945. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

Donald Trump, like Frank Meyer, did not originate all of this as a novel idea. He inherited it. Trump’s slogans were derived from Pat Buchanan’s 1992 presidential run (and many of Buchanan’s slogans were derived from Ronald Reagan and previous candidates). It continues a long tradition on the right. Meyer, who pressured Republican Mr. Bob Taft in 1952 to such an extent that he lost his freelance job in the free man when the magazine’s board of directors fired its anti-Eisenhower editors, it absorbed their foreign policy perspective from the Ohio senator and others.

Trump, as he demonstrated in Iran, Ukraine and elsewhere, is not an isolationist. Nor, of course, the fiercely anti-communist Meyer.

Common sense conservatives avoid hiding. They also hate adopting an “I’m-from-the-government-and-I’m-here-to-help-you” mentality.

Washington understood that, even if the city that bears his name rarely does. So did Taft, Meyer, Buchanan and Trump.

Daniel J. Flynn is the author of The Man Who Invented Conservatism: The Improbable Life of Frank S. Meyer (ISI Meeting/Books) and visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution.